650-years-ago, when the mighty, martial Edward III had been on the throne for over 40 years, and all Europe was still reeling from a pandemic immeasurably worse than our own, a group of Londoners engaged in the making and selling of wax candles and sealing wax decided it was time to get organised. Their craft, they said, had been ‘evill ruled and governed afore this tyme’. Accordingly on 13th November 1371, they applied to the City’s governing body, the Mayor and Court of Aldermen, to have officials appointed from among their number (masters) to ‘overse all the defaults in theyre saide crafte’, and see that offenders were prosecuted. Some regulations about charges and manufacture were appended for the court’s approval.

On the following day (14th November), Walter le Rede and John Pope were duly appointed as the first overseers of the Wax Chandlers’ ‘mystery’ (craft guild), and the ordinances were ratified.

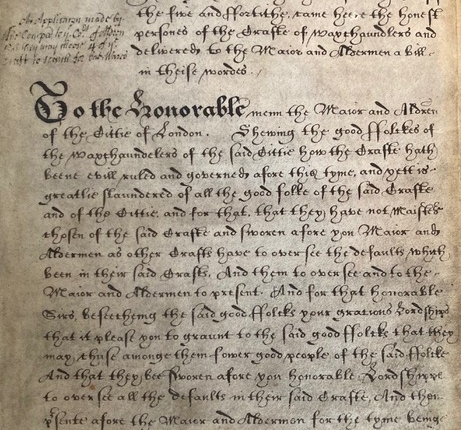

The Company’s record of the approval of the 1371 ordinances is a copy of the petition, entered on the first folio of the Charter and Ordinance Book of William Sharp, Master in 1622 (Guildhall MS 9496), and on the 8th folio of another register of ordinances (Guildhall MS 9495). It is also enrolled in the City’s official records (Letter Book G f. 283).

What had previously been an informal association of chandlers, fending for themselves without any proper structure or apparent backing from the available power bases, the City, the Crown or the Church, was now given authority by the Mayor and Aldermen, paving the way for the emergence of a fully- fledged City company, with the grant of a royal charter just over a century later. Wax would never make it into the big league, the Great Twelve, dominated by the powerful mercantile and victualling associations, the Mercers, Fishmongers, Grocers, et al, but, they were at number 20 of 48 when the order of precedence, was set in 1516; the determining factor being wealth rather than antiquity.

14th November 1371, then, may be regarded as The Company’s birthday.

London in 1371

It was only 21 years since the Black Death had wiped out half the city’s population, leaving houses and workshops empty, looms and mills still, altars untended, markets abandoned. Bodies were stacked 5 deep in the plague burial ground near the Tower, at East Smithfield, one of several created for the emergency. Presumably the losses among the Wax Chandlers’ community was very high as they were much involved in funeral rites. Between 1348 October 1349 one third of aldermen perished; eight wardens of the Cutlers Company died in four months in 1349; of 118 apprentices enrolled in the Goldsmiths’ Company between 1342 and 1346, 90% had disappeared from the company’s records by 1350. And it was still not over. There were further waves in 1361-4, 1368-9 and now another would soon be starting which would carry on until 1375. Although the death toll in these later waves was much down on 1348-50, they brought a new horror, preying on children and young folk, apprentices rather than masters. In 1357 Londoners had claimed that one third of their city’s properties were vacant and 30 years after the peak of the pandemic some houses were still ‘empty and void’. The population would not return to its pre plague size for well over a century.

But, like swinging London emerging from the Blitz, the City bounced back from the onslaught with extraordinary resilience; it was soon a bustling place again, a thriving port, the largest city in the kingdom, by far, though only the size a small market town is today. It was an important industrial and commercial centre, noticeably cleaner than it had been before the pestilence, still parading its wealth in bright silks and glorious civic pageantry. These were good times for the peasant and artisan, with the population halved, labour was in short supply and wages rose dramatically. The income of ordinary folk was relatively greater than at any time until the 19th century, especially in London where wages were 25% higher than elsewhere. As trade flourished the merchant and craft guilds proliferated and labourers and merchants alike were increasingly drawn towards London where, it was said, the streets were paved with gold.

The suburbs had begun to sprawl out to the east beyond the Tower, west, along the Strand joining with Westminster, now the kingdom’s administrative capital, and south of the river in Southwark, but it was within the square mile of the walled city where most of the inhabitants lived and worked, possibly 40,000 of them. There the air rang with the sound of hammer on anvil, the rattles of carts, the clip of hooves, and the constant tintinnabulation of bells-there were 107 churches squeezed within the walls of the square mile. Over all towered the tallest spire in Europe, crowning the vast cathedral of St Paul’s. You would have encountered, among the throng of artisans and merchants, old soldiers back from France, apprentices and serving girls, any number of religious personnel about their business, randy monks, crooks, conmen, and hypocrites, if Chaucer is to be believed. But piety is not much of a subject for a satirical poet and, moreover, he was in sympathy with Wycliffe and his attacks on the immorality and corruption in the church.

At the City’s heart was the wide piazza – like Cheapside, where stood the great stone cross erected by the King’s grandfather, a focus for processions and pageants. Merchants’ mansions, guild halls, shops, and stalls lined the main thoroughfares and off them wound narrow, higgledy-piggledy lanes, some only six foot wide, with overhanging houses that nearly met, workshops and cottages jostling for space. Pigs, stray cats and dogs wandered about, and there were fast food outlets on every corner –hot pies and spiced ale.

Craftsmen and traders congregated together to sell, work and live in occupational groups; we still have streets named accordingly: Poultry, Milk Street, Bread Street etc. The Candlemakers, too have left their mark, but it is not immediately recognisable. Cannon Street is a corruption of Candlewick Street, the westward extension of the main market and thoroughfare on the east side of the City, Eastcheap. A ward (administrative division), in this part of the City still bears the name ‘Candlewick’. The earliest reference to the name is 1180, which suggests that the candle men (wax and tallow), had taken over this part of town some years before. John de Benstede, the first apprentice to the trade who appears in the records, was bound to John le Cirger of ‘Kandelwickstrete’ in 1291/2. Wax Chandlers William Cirgere (wife’s will 1333), and Thomas Fraunceys (will 1348), lived in the street, as did John Pope, one of the two ‘masters’ appointed in the ratification of the 1371 ordinances.

According to the poem London Lickpenny (c. 1410), London was one continuous, grasping market. In Cheapside, the Kentish farmer who is the hero, saw ‘moche people’ and was pressed to buy fine linen and ‘Paris thred’. In Candlewick Street (now dominated by drapers), he was offered cut price cloth, cod, mackerel and steaming hot sheep’s feet. Lively fun was to be had in nearby Eastcheap, where pies and ribs of beef might be washed down with tankards of ale, accompanied by ‘harp, pipe, and minstrelsie’, popular songs and a good deal of swearing – all for a price, of course. Cornhill market went in for ‘stolne gere’ and at Billingsgate our country bumpkin had to shoo hens away to get to the ferryman. In London anything might be bought, and nothing could be achieved without a purse full of silver.

But this was no free for all; the rulers of the City were fierce and forceful. As well as numerous petty regulations: no walking about after curfew time, no selling of sweet wine in the same tavern as dry wine, shoes to be of a certain quality leather etc. trading standards were rigorously enforced and woe betide anyone who contravened them. There was a positive obsession with health and safety as far as food was concerned; the City fathers were especially vigilant about stinking meat and fish and the size, weight and contents of loaves of bread; the mayor might even supervise the weighing of loaves himself. Punishments were harsh and public; bakers might be dragged on hurdles through the streets, before they were flung into Newgate. Offending butchers and fishmongers were put in the pillory with the bad food burning in a fire underneath. A chandler found guilty of dealing in adulterated wax had the mayor’s ‘heavies’ come and make a fire of the sub-standard wares on his doorstep. He was then either fined, put in prison or the pillory.

A hundred years before the City had been in the hands of a small group of patrician landowners, of whom some might have been involved in trade as a sideline. But now it was merchants who called the shots. The trade and craft guilds had been around in some form or another since before the Conquest; it was over 200 years since the London weavers and the bakers had first secured a right of monopoly from the crown. Now a whole range of trades were coming into their own, controlling their own practices and taking an increasing share in local government. In 1312 the aldermen and ‘good men from every mystery’ agreed that freedom of the City, without which a man could not practice his trade or craft there, would only be granted if he was vouched for by representatives of the business he wished to join. All through the reign of Edward III (1327-77), there was a steady grant of royal charters. From 1376 to 1384 members of Common Council (the City’s ‘House of Commons’), were actually nominated by the crafts instead of the wards. Old feudal mansions were bought for the companies’ all- important feasts and meetings, or brand-new halls built. The Wax Chandlers would wait over a hundred years before they got theirs, a converted brewery, called, as many were, ‘The Cock on the Hoop’.

Ordinances and fraternities

Between 1322 and 1396 no less than 37 craft companies brought ordinances or rules for self-government (sort of proto charters), to the mayor for ratification. Most of them, like ours, had provisions for the election of wardens or masters and for the detection of sub-standard goods or workmanship. The Wax Chandlers were not alone. Probably the trigger for so many crafts to smarten up their act was the new ruling about freedoms, which called for corporate action. A stamp of approval from the City authorities was very much cheaper and more straight forward than going for a royal charter. That was, of course, the ultimate prize, if achieved, it allowed a guild to become a company by licencing it to hold property in perpetuity in the name of the organisation. Royal backing was always a good idea; it opened many doors.

Another route for a trade / craft guild to take to gain credence and respect, possibly even more important than getting authorisation from the secular powers, was to take shelter under the protective wing of Holy Mother Church. ‘The right of pursuing economic ends by voluntary association’ wrote George Unwin in 1908, ‘was not recognised in the medieval city’ and the government was always jittery about ‘combinations’. Nearly all the London guilds were linked with a religious fraternity or brotherhood; in some cases, they merged. The Painters’ ordinances included a directive that anyone joining their guild was required to give two shillings to the confrarie for the poor of the mystery. Some companies, like the Brewers, actually evolved from one, starting life in 1342 as an association of parishioners who came together to raise money to repair a chapel at All Hallows London Wall‘ in honour of Jesus Christ who hangs on the cross’. By 1388 it was a Brewers’ Guild. In 1345 twenty-two spice dealers of Soper Lane founded a fraternity in honour of St Anthony. At the inaugural feast, all dressed in matching ‘livery’, they made the decision to hire a priest to ‘chant and pray’ for the members and to give a penny each a week to pay him. Anyone of substance could join, so long as he practiced the same trade and paid 13s 4d. Within a few years this organisation had become the Grocers’ Company, one of the most powerful of all. They did not bother with a royal charter until 1426.

This coming together of trade associations and praying / social clubs might seem to us a miss-match, but it was still an age of faith, when nothing was done that was done without invoking the blessing of the Almighty. Religious fraternities were very popular in the 14th century and would become more so until they were abolished at the Reformation. Every church had several, the larger churches had a multiplicity, dedicated to Our Lady, assorted saints (St Katharine was the favourite), the Holy Cross, the Trinity and various aspects of Christ, his body, his name, his crucifixion. By 1500 there are said to have been about 200 in London; there could have been many more.

Little is really known about these essentially secret societies, and it is difficult to gage exactly what their purpose and origins were. Most City churches would have had a membership of 3-400 and joining a select club, within it, brought a feeling of belonging and involvement to a laiety largely excluded from the sacred rites. They had their own chaplain, a private saint or object of veneration, their very own altar or chapel, a periodic rollcall of loved ones and friends and splendid feasts. One of the chief functions of the fraternities was the provision of poor men’s cheap co-operative chantries; special masses were celebrated when the names of the deceased members of the brotherhood were read out. Instead of leaving a large sum in your will for masses to be said to help get you and yours out of purgatory, you might pay a few pence to the fraternity who offered a cut-price service. There were other more tangible benefits; the Brotherhood [brithrid] of Jesus at St Botolph’s Aldgate funded funerals for those who could not afford it and in 1346 the fraternity attached to the Whittawers’ (leather dressers), offered 7d a week to any member who could not work, through sickness or age and 7d p.w. to his widow when the time came. Like any exclusive club, they had their own rules and practices: members of the Guild of Holy Trinity at St Botolph’s Aldersgate were expected to greet one another in an especially friendly way; the fraternity of St St Anne at St Laurence Jewry was strict about membership and threw out lie-a-beds and tavern haunters.

With membership came status, as Chaucer made clear; among his pilgrims were a haberdasher, a carpenter, a weaver, a dyer and a tapestry maker, ‘And they were clothed alle in o[ne] lyveree of a solemn and a great parish guild’. Joining a fraternity might be the first step on the social ladder and the start of a shopkeeper making his mark. For a trade to link up with its local parish club was an obvious step.

In some cases the initiative in setting up a fraternity came from the church itself, especially when the raison d’etre of the fraternity was the raising of money to repair fabric or supply ornaments, as at All Hallows London Wall (above). When John Colet, Dean of St Pauls, set about reforming the Guild of the Holy Name of Jesus in the mid-15th century, he said it was in order to strengthen the bond between Londoners and their cathedral.

It was de rigeur for the crafts to have the support of the church. When, in 1396, the cockey ‘serving men’ and journeymen of the Saddlers’ Guild made a bid to get their masters to double their wages, by forming themselves into ‘covins’ (combinations), they did it under the cloak of a fraternity dedicated to the Virgin. On the day of the feast of the Assumption they processed from Stratford (where their headquarters seems to have been), to St Vedast for a special mass, all attired in their very own livery. The masters reckoned that it was self- interest clothed in piety, done under the ‘feigned colour of sanctity’ [Memorials, 1396].

To return to Wax, the chandlers did not, as far as we know, immediately sign themselves up for a fraternity as such, which is strange, considering they were, as we shall see, very much bound up with the church day to day in their work. However, it is worth noting that the first material entry in the ordinance, oath and evidence book, before the 1371 ordinances, on the same page, is an agreement with St Paul’s, also dated 1371. A ‘company’ of chandlers undertook that each of them should give to the cathedral at least a pound of new wax, some more, every year on Holy Cross Day. It was to be used for the tapers (large candles) in the candelabrum of the crucifix over the north door, called the ‘Rood of Northern’. This might seem no big deal to us, but it is given pride of place in the company’s register of important documents and there may be more to it than meets the eye.

The undertaking to maintain lights at an altar or shrine was the invariable first step in the forming of a fraternity – and this was no ordinary shrine. The ‘Rood of Northern’ attracted enormous veneration countrywide, bringing in a considerable income for the canons, in gifts of money and jewels. Supposedly brought by Joseph of Arimathea, the bigger than life size cross was mounted on a huge wooden platform at the north door of the cathedral, approached by a flight of stairs and flanked by two altars to of St Margaret and St James. In later years (1465), John Paston would urge his mother to take his sister Margery to pray at the rood of northern so that she might get a good husband.

By agreeing to keep the show-piece crucifix lit, the Wax Chandlers were obviously eliciting from the cathedral the all-important ecclesiastical backing for their guild, but there is no further evidence of any special relationship with St Paul’s until the early years of the 16th century. Then the Chandlers would become closely involved with the Jesus Guild, a most prestigious affair, with a full complement of staff, its own organ, its own setting of the mass, banners and bonfires, its chapel in the crypt blaze with the continual light of hundreds of candles. In return for supplying wax the company received liveries embroidered with the sacred monogram (HIS), regular prayers for their dead, special masses, and a venue for their annual elections.

The lack of any documentary evidence for a special association with St Paul’s in the intervening years is not necessarily conclusive. Hardly any original administrative records of the company survive from the medieval period, and it is rare in the extreme for any of the secret fraternities to make an appearance in City records. So it is possible that there were links between the cathedral and Wax Chandlers that we know not of. John Pope, one of the two masters appointed in the 1371 ordinances, was buried in a family tomb in St Paul’s churchyard.

A boom time for wax

If the late 14th century brought, as the chronicler said, ‘good times’ for the City’s trade guilds, it was a boom time for Wax like no other. The ‘new normal’ in the aftermath of the Great Mortality featured changes in religious practices which would bring silver and gold clattering into the coffers of the wax candle makers of the realm. Wax chandlery was a luxury trade; it was lords and rich merchants that illuminated their grand halls with the pure light of beeswax, while the peasant and artisan cottage was lit with what Shakespeare called the ‘base, unlustrous, smokey light’ of stinking tallow (animal fat). Tallow was cheap. The Wax Chandlers’ biggest market, was the church and the death industry.

It seems to have been in the 12th century that there emerged an independent trade of chandlery, the making and selling of candles, wax and tallow, for the most part, keeping themselves to themselves. This, as far as we can tell, with the scant records that survive, was the case in London, although in other parts of the country the two crafts formed joint guilds. In the past candles had been made in-house by servants and monks, and large organisations, like the royal household, had their own chandleries. By the 13th century personal names like Cierger and Serger and Le Chaundler start to appear in the records; a cierge was a wax candle, from the Latin cera; the name le Chaundler could apply to both wax and tallow chandlers, but is more commonly associated with the latter. In a 1319 tax list eleven Wax Chandlers appear in the City. Each probably had a shop and a workshop; it is unlikely that there were any beehives, whereas tallow chandlers were often concerned with the production of their raw material, the rendering down of fat, medieval wax chandlers seem to have bought in their beeswax, much of it from Flanders.

By 1330 the wax chandlers were enough of a cohesive body to be one of the 20 mysteries invited to subsidize the King’s wars against the French. Their ‘gift’ was duly made, 4os, as opposed to the £40 given by the Mercers! In 1358 ordinances concerning the adulteration of wax were issued by the City authorities; whether or not this was at the instance of the trade itself is not apparent. The significance of the 1371 ordinances lies in the appointment of two named, permanent officials – the first masters.

After the Black Death the world was turned upside down: the lower orders, their labour now much in demand, were getting above themselves, earning enough to dress like their betters. Parliament re-enforced and extended the old sumptuary laws: only the ladies of knights with a rental above 200 marks a year might wear fur; there were to be no silk veils for yeomen’s wives. Thirty years after the peak of the pandemic, Wat Tyler led the first revolt of the common people. More important than any of this for the Wax Chandlers was the seismic change in how men and women dealt with death.

One might imagine from Chaucer’s ‘Wycliffite’ propaganda and the ex post facto assessments of many later observers, that this was the beginning of the end for the Catholic church in England. A corrupt, avaricious, and rotten institution would be ripped apart within 200 years. But 200 years is 200 years and, arguably the late 14th and 15th centuries were a time of greater devotion and piety than any other in these islands. The loss of perhaps half of the people in their world, brought to men and women quite a remarkable preoccupation with the afterlife. A frenetic religiosity took hold; millions of pounds were spent on priests and masses, on church buildings and on steeples, and on bells, and on candles.

Central to all this was the notion of purgatory, the half-way house between life and heaven and hell, where souls went for cleansing. As real to the men of our mystery as the any television documentary might be to us, it was seen as a wide-open space, full of wheels of fire, where the dead called out to the living to save them from torment. Would you not, asked Sir Thomas More, reach out to snatch your mother from the fire?

Time out of purgatory could, quite simply, be purchased, for yourself and your nearest and dearest. Wills of the period make quite astonishing reading. Huge sums of money were left to fund chantries; shops and houses were directed to be sold and the profits used to buy the services of priests. It was not uncommon for rich City merchants and their wives to instruct their executors to send a priest on a trip to Rome, at the estate’s expense, to offer prayers for their souls at the centre of Christendom. In churches and abbeys throughout the realm there was a constant hum of prayer, and a continual flickering of candles. Chantry priests sang for the souls of the dead, day and night, saying masses for the men and women who had commissioned them, to rescue their loved ones from the fire and ensure their own place in paradise. The going rate was 4d a mass and 10s for a trental, the popular marathon of thirty masses. Indulgences (tickets to get you or yours out of purgatory), might be bought for cash or obtained through various exercises. The frontispiece of a mass primer found in the convent of Syon near Isleworth promised 32,755 years’ worth of indulgence to those who recited a modest number of prayers while looking at the woodcut of the suffering Christ there displayed. Funerals would become more and more elaborate; when Richard II’s Queen died in 1394 ‘an abundance of wax’ was brought from Flanders for the torches and tapers. At the lying-in state of Elizabeth of York (Henry VIII’s mother), 10,000 torches lit the way and 500 tapers were placed around the bier.

The newly popular cult of the rood meant more demand for large, expensive lights. Every church had a great crucifix lit with ‘footlights’ for dramatic effect. Every fraternity had its shrines and its processions with torches. Old Alice Paston of Norfolk ordered a wax image of her sick son, matching his weight, for the shrine of Our Lady at Walsingham (1443). The wax industry was given a terrific boost by the on-going demand for candles and torches, wax images of saints and relatives. Chandlers did not just sell candles, they set up displays for funerals and obits, and supplied all the necessary equipment, notably the iron candle stands, known as hearses. In 1422 Wax Chandler, Simon Prentot’s charged an astronomical £300, the equivalent of perhaps £200,000 for setting up hearses in various locations in London, Westminster and Kent to mark the death of Henry V. In 1433 parliament became concerned about the exactions: ‘In divers Parts of England’ they ‘sell Candels, Images and Figures, and other works of Wax made for offerings 1js and more, where one Pound of Wax is no more worth than vjd…by which Means divers of the People be defrauded of their good Intent and Devotion’. The chandlers were ordered to ‘charge no more than 3d in the pound for image wax than for plain wax’ (11 Henry VI c. 12). When Henry VIII’s Lord Chancellor, Thomas Audley, died, he asked for ‘as little pomp as conveniently may be’. The wishes expressed in his will were evidently ignored, Wax Chandler, Robert Thrower supplied a ‘hearse of wax’ for which he was not paid but agreed to forgo the cost until the sum could be raised from the deceased’s lands. It must have been some funeral bill.

As John Noorthouck wrote in the 18th century, wax chandlery was ‘a very profitable business in Popish times’. But it would come to an end. The Reformation caused a crisis in the trade and in the company; Wax Chandlers membership slumped from 54 in 1531 to a mere 34 in 1538. As one man put it, purgatory was ‘pissed owte’, chantries and fraternities were done away with, crucifixes and their footlights came crashing down and a myriad candles were snuffed out. An injunction of Edward VI reads: ‘they shall take away, utterly extinct, and destroy all shrines, covering of shrines, all tables, candlesticks, trindles or rolls of wax…’; a trindle was a taper consisting of a long thin coil of wax. When Bloody Mary tried to bring it all back she had a 300 lb candle put at the altar of the Confessor at Westminster Abbey.

The contents of the 1371 ordinances

The first, and major concern in the 1371 ordinances seems to have been the manufacture and sale of wax which was bulked up with cheaper materials, like tallow and resin. Adulteration was common; wax was a luxury item, costing sixpence a pound, the price of a good pair of shoes or a day’s wages for an artisan. ‘ Deceitful mixtures’ was something which the City authorities were always concerned about. Only 13 years previously (1358), ordinances had been issued on the subject when an influential Italian spicer and apothecary was found to have made a ‘false torch’, causing quite a scandal. The punishment in these earlier ordinances was imprisonment, a fine or a spell in the pillory; persistent offenders were to ‘forswear the city, and all torches and such work.’

The 1371 ordinances list the fines for dealing in adulterated wax: for the first offence the chandler had to pay 6s 8d (half a mark), into the City’s chamber (bank); for the second offence the fine was 13s4d (a mark) and for the third 20s (£1). If a chandler offended for a fourth time he must ‘forswere the crafte for evermore’.

Ordinances 2 to 6 fixed 9d per pound of wax as the sum to be charged for the hire of candles and their iron stands (hearses), for funerary rites and ceremonies; Candlemas was specifically mentioned. The candles listed are: tapers (large candles), torches (twisted tow or cotton soaked in resin and coated with beeswax), square funeral candles (quarerres), torchettes (small torches), prykettes (candles that go on spikes), and perchers (tall candles for altars). If the customer supplied his own raw material, the chandler was to charge a halfpenny per pound of wax for his services. Finally, for reasons of quality control, every City chandler was to have his own identifying mark, with which the wax items were to be stamped.

The two masters or overseers appointed in the ordinances were obviously well-established men of the craft, Walter le Rede had been appointed as an inspector in the 1358 ordinances and John Pope would become the craft’s representative on Common Council in 1376. Apart from those two appointments, what little is known about them comes from their wills. Neither of them appears to have had great wealth or any living children.

Walter le Rede probably lived in the parish of All Hallows Bread Street, though he asks to be buried in St Paul’s churchyard. There are no children mentioned, only a dead stepdaughter. He evidently belonged to a fraternity dedicated to Saint Giles and St John; there was one such at St Giles, Cripplegate, but there way very well have been one at All Hallows. His wife was called Gonnora, his sister, Alice, his servant, John. The division of his estate into two parts was the norm, half for his wife and half at his personal disposal, called the ‘soul’s part’. The latter was regularly devoted to charity, either to the church for masses, or to a hospital or monastery, or, quite often for the upkeep of roads or bridges. If a man had children this ‘soul’s part’ would usually be one third of his estate. If the ‘pious uses’ are not specified, it would be left to his executors to make the arrangements. Walter’s charitable bequests are quite standard: his parish church, the friars, the fabric of St Paul’s, the nuns of Bromley Priory (where Chaucer’s prioress spoke French ‘After the scole of stratford atte bowe’.):

Rede, Walter, “wexchaundeller”. — To be buried in S. Paul’s churchyard in the tomb where Agnes, daughter of Gonnora his wife, lies buried. His goods to be divided into two parts, whereof he leaves one to his said wife, and out of his own share he makes various bequests to the rector of the church of All Hallows in Bredestrete for the time being, the old fabric of S. Paul’s, the five orders of friars in London, the nuns of Stretford, anchorites, &c. To Alice his sister five shillings and two silver spoons. To John his servant a cloak of red, another cloak (armilausam), lined with russet and medle, two hoods of the livery of SS. Giles and John, and eighteen shillings. Dated London, 21 July, A.D. 1375.

John Pope’s will, too, is a very standard document. His house is in Candlewick Street and is left to his wife, Elizabeth, for life, as was the custom of London, thereafter it was to be sold to a fellow Wax Chandler and the proceeds devoted to pious uses, in this case unspecified. As his deceased relatives are named it suggests that the money might have gone for masses for his and their souls. The only child mentioned is his daughter, Goda, who has died. John Pope was on his fourth marriage. Even by medieval standards this is unusual; two or three was not uncommon, but four wives – nearly as good as the Wife of Bath -and no children to show for it!

Pope, John, “wexchaundeler.”—To Elizabeth his wife his tenement in Candelwykstret at the corner of S. Clement’s Lane in the parish of S. Clement near Estchepe for life. The reversion of the same to be immediately sold, William Fynch, “wexchaundeler,” being preferred purchaser to all others, and the proceeds devoted to the good of his soul, the souls of Johanna, Mary, and Mary his late wives, the welfare of Elizabeth his wife, the souls of Goda his daughter, John his father, Alice his mother, and others. Dated 12 May, A.D. 1402.

When Walter le Rede and John Pope and their fellows launched their enterprise in 1371, they could not have anticipated that their guild would still be flourishing 650 years later. It wears a different guise, not so much concerned with the ancient craft for which it was created, but sharing its aims, perhaps, with the London branch of an early 14th century guild of French and English merchants, the Feste du Pui, set up ‘For the safeguarding of loyal friendship, to the end that the city of London may be renowned for all good things in all places, and that good fellowship, peace, honour, gentleness, cheerful mirth and kindly affection may be duly maintained’.

Jane Cox

Liveryman

SOURCES

Calendar of Letter Books of the City of London, G & H @ British History on line.

Caroline Barron, London in the later Middle Ages, 2004.

Sharon N. DeWitte, ‘Mortality Risk and Survival in the Aftermath of the Medieval Black Death’, May 7, 2014 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0096513.

Jane Cox, Old East Enders, 2013.

John Dummelow, The Wax Chandlers of London, 1973.

Guildhall MSS 9495 & 9496.

Hustings wills @ British History on line.

ed. Derek Keene, Arthur Burns, Andrew Saint, St Paul’s The Cathedral Church of London, 2004

Randall Monier-William, Tallow Chandlers of the City of London. Vol II, 1972.

John Noorthouck, A new History of London, 1773.

The Paston Letters.

PCC wills @ TheGenealogist.

Barney Sloane, The Black Death in London, 2011.

The National Archives: C1/1147/90 for Audley’s estate.

George Unwin, The Guilds and Companies of London, 1908.